Framework Overview

Summary

This section of the guidebook provides an overview of ecosystem services assessment methods that could be applied across geographies and decision contexts and shows how they fit together. It will help managers incorporate the effects on ecosystem services of different management alternatives or scenarios, policy options, and locations of actions or infrastructure. It will also help with the development of performance metrics and may suggest changes in data collection and monitoring. The overview contains links to more detailed discussions of assessment methods in other sections of the guidebook as well as to additional resources.

Takeaways

- Ecosystem services should be used if decision makers want to go beyond an assessment of ecological conditions alone to consider how changes in ecosystems affect people.

- The ecosystem services assessments combines insights and methods from the natural social, behavioral, and economic sciences.

- The methods described in this guidebook can be applied flexibly to meet decision-maker needs.

What are Ecosystem Services Assessments and Who Will Use Them?

Ecosystem services assessments can be used to describe how management choices affect the well-being of people, communities, and economies through their effect on natural systems. Ideally, such an assessment will help decision makers incorporate the less commonly quantified but no less important benefits of nature, along with more commonly considered benefits of management actions, into their decision making.

The ecosystem services assessment methods described in this guidebook apply primarily to regional-, local-, or project-scale decisions affecting actual locations. They can be applied in different geographies and with different levels of expertise and resources. They can also be adapted and used in a wide range of decision contexts, including

- Species or biodiversity management,

- Ecological restoration or conservation (approach or location),

- Risk management (reducing floor, fire, or storm surge risks),

- Infrastructure decisions and siting (roads, housing, trails, campsites, energy production, mining, pipelines, etc.),

- Selection of performance metrics, and

- Identification of data and monitoring needs.

This overview of methods is designed to help managers explore simpler and more accessible methods for ecosystem services analysis, building toward the use of more quantitative and in-depth approaches over time. Although the overview depicts a relatively linear process for putting these methods together, the actual process of incorporating ecosystem services considerations into decision making is likely to be iterative.

Best practices for using ecosystem services assessments can be found in this companion paper.

How Does This Overview of Ecosystem Services Methods Fit in with Other Decision Support Guidance?

The ecosystem services assessment methods described here are generic and align with many other decision support frameworks under development or already in use by academics, NGOs, and consultants (e.g., The Natural Capital Project, The Open Standards approach, and World Resources Institute’s Ecosystem Services Guide for Decision Makers). Several agencies have also produced or are working on ecosystem services frameworks or guidance that follow similar steps and use similar methods (e.g., the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Forest Service.)1

By providing a relatively complete overview of common methods for incorporating ecosystem services considerations into decision making, this guidebook aims to improve consistency and validity in applying these methods across federal agencies and to help agencies customize ecosystem services analysis to meet their needs and decision contexts.

The FRMES ecosystem services assessment methods review

- Provides examples of integrating ecosystem services into existing federal planning processes from project scoping through monitoring of decision outcomes;

- Emphasizes how ecological changes result in changes in the provision of ecosystem services and benefits to people;

- Provides detailed information on methods to assess changes in ecosystem services, including guidance on quantification and valuation;

- Provides flexibility in application from quantifying the benefits (what is valued) to quantifying the preferences and values people have for the benefits; and

- Is consistent with other frameworks as well as existing software and downloadable tools (e.g., Miradi, InVEST, ARIES, Envision).

The methods presented in this guidebook are designed to be useful across geographies, natural resource priorities, and all types of ecosystem services and to be applicable to a range of decision contexts important to federal agencies. Although most obviously applicable to decisions that directly target natural resource issues, consideration of ecosystem services can be salient to any decision that directly or indirectly affects ecosystems, natural resources, or the environment. For example, ecosystem services might be useful in tracking performance of programs and projects to assess progress toward goals; in comparing outcomes to better allocate future funding; in considering the potential effects of proposed natural resource and infrastructure plans, siting decisions, or permit allocations for use of public resources; and in revising rules and regulations that drive implementation of laws such as the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act.

This review of methods is intended to help managers across federal agencies design decision processes that incorporate ecosystem services, to help them fit the methods to their needs, and to understand the expertise needed to apply them.

Ecosystem Services Assessment in Decision Processes

This guidebook organizes the ecosystem services assessment methods around an example planning process using four general stages: (1) scoping, (2) analysis, (3) the decision, and (4) reaction (Figure 1). These stages also occur in other comprehensive decision-making approaches, such as economic valuation and structured decision making, elements of which are included in this framework.2

Figure 1. Generic decision process with ecosystem services assessment embedded

Note: Integrating ecosystem services considerations into the decision making process—that is, translating ecological changes into implications for people—requires changes throughout the decision process, particularly in the scoping and assessment phases. Stakeholder engagement continues through the full decision process.

This section of the guidebook emphasizes what is new about incorporating ecosystem services relative to standard ecological assessments. It describes how ecological information and stakeholder engagement are used together to inform ecosystem services priorities in the scoping process. It also describes methods for assessing how ecological changes matter to people, including approaches for integrating social preferences, and procedures for comparing options. The resulting information on ecosystem services feeds into the decision process.

Scoping

Scoping is the process of identifying an initial set of desired outcomes and management objectives based on an assessment of ecological and social data on past management outcomes, current conditions, and anticipated future needs. This stage might include problem definition and needs assessments. It may include a significant component of stakeholder engagement. In a federal agency context, Congress, the Office of Management and Budget, and departmental and agency policy generally set the sideboards for the set of desired outcomes and management options to be considered. Consideration of ecosystem services can be integrated into these assessments of problems and needs by connecting the ecological outcomes to people.

In a typical planning process, scoping would entail an analysis of ecological status and trends, which would include information on ecological conditions and potential threats and stressors over time for the area of interest. For example, such an analysis might include information from FIA and LANDFIRE databases status and trends of forestlands (e.g., forest growth and forest departure from natural conditions due to fire suppression). It might also use local monitoring data, research findings, or field evaluations from resource staff to assess ecological conditions. Ideally, scoping will also incorporate landscape-scale or regional information about larger-scale processes that will affect or be affected by the decisions at hand. A focus on ecosystem services in this scoping phase would extend a typical status and trends assessment to an entire affected area (e.g., watershed, airshed, fishery) in order to encompass the flow of services to and from the resource management area to the people who are affected.

Scoping often involves an assessment of user needs, perhaps involving meetings with stakeholder communities (within the bounds of regulatory limits, e.g., the Federal Advisory Committee Act). The result is a set of desired social outcomes that, when incorporating ecosystem services, can be described as ecosystem-service-derived benefits.

A focus on ecosystem services requires an explicit connection between the desired ecological conditions and how these conditions will affect people. For example, when assessing policies to address forest fire risk, ecological conditions might be described in terms of changes in fire frequency and resulting changes in forest structure and species composition. To make these changes more meaningful to people, the ecosystem services might be described in terms of enhanced populations of species of interest (e.g., bison on the prairie, birds to watch, fish to catch), increased opportunity to hike and camp in the forest, decreased incidence of smoke, and changes in the provision of wood. This is an example of a conceptual mapping exercise focused on ecosystem services. Such conceptual maps or diagrams will play a critical role in helping managers and assessors identify services to include and thus beneficiaries to consider or engage in an assessment process because they make explicit the connection between ecological conditions and benefits people derive from them.

When stakeholders are engaged directly, they can be asked to identify what they value in a given planning area. Such expressions provide initial qualitative evidence of the ecosystem-derived benefits (the ecosystem services) they would like to obtain or experience. The scoping process is likely to be iterative, linking desired ecological conditions and desired social outcomes. This process will help managers identify the management objectives and options that have the capacity to achieve both ecological and social objectives. The stakeholder engagement process is likely to capture a range of opinions about which outcomes are valuable. Reconciling these different opinions and evaluating tradeoffs are fundamental components of assessment and decision processes. Another key issue is balancing stakeholder preferences with the need to sustainably manage ecological processes over time. The stakeholder process complements program mandates and legal constraints, which also drive policies and options considered.

Once desired management objectives (ecological conditions and social outcomes) are determined, the next step is to identify a set of management alternatives, project options, or policy choices for achieving those outcomes and perhaps to identify performance metrics and measures. For example, within the context of forest fire management, managers might want to use prescribed fire and removal of invasive plants (management actions) to help reestablish healthy longleaf pine forest (desired conditions) in the southeast. Managers may need to decide where to use these actions to best enhance wildlife viewing and improve recreational opportunities while minimizing smoke exposure (desired social outcomes). Other decisions might involve choices between different management actions: understory thinning versus prescribed burning to alter forest structure and reduce fuel loads or a levee versus floodplain restoration to address flooding. In other policy contexts, decisions might involve policy choices such as changing water releases from dams or establishing incentives programs for biomass energy. These could be ecosystem service assessments so long as the policies can be articulated in terms of likely changes to both ecological conditions and ecosystem services. At this point conceptual maps and causal chains can be created to help connect agency actions to the ecosystem benefits identified as important.

Conceptual Diagrams

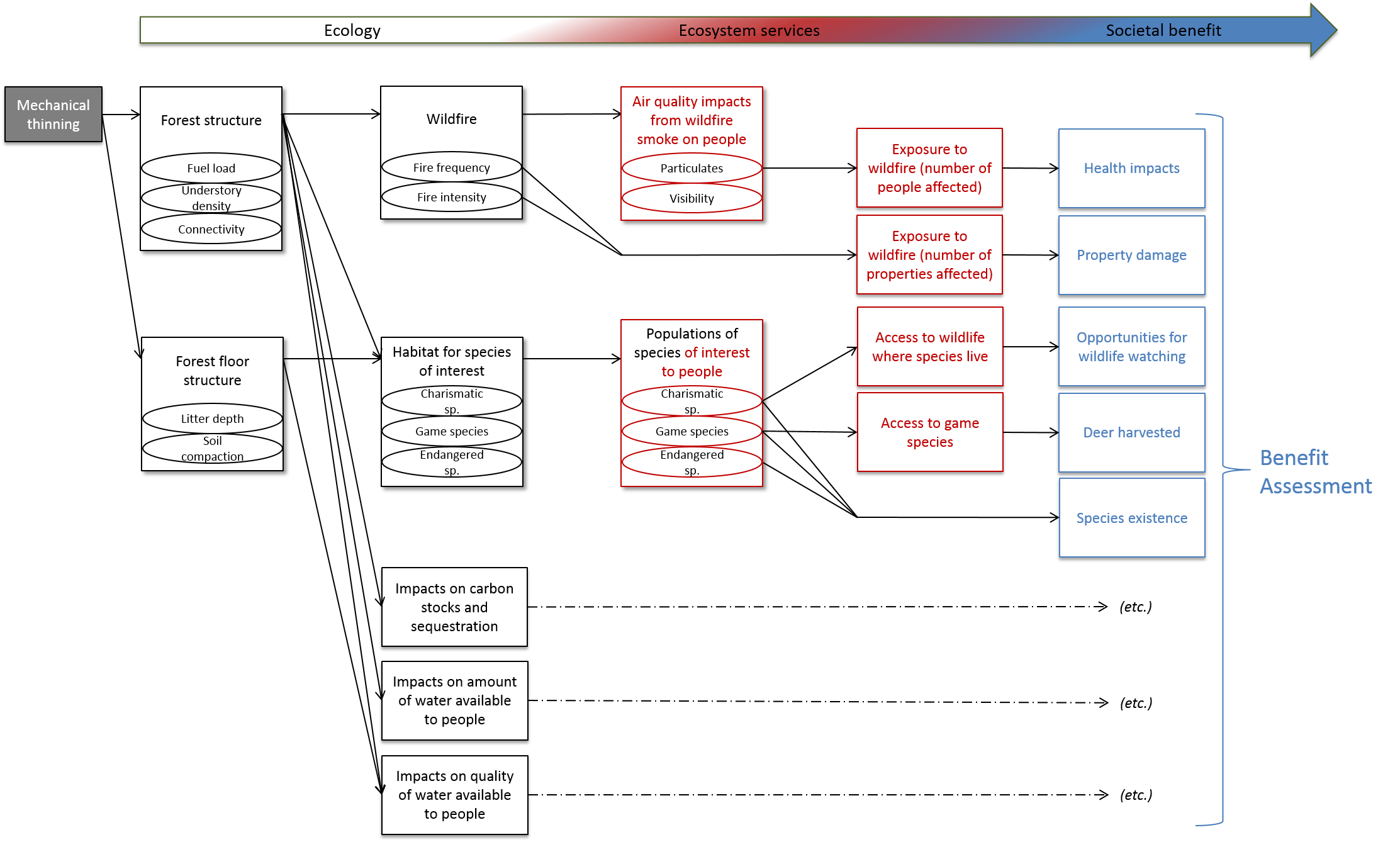

Many decisions require assessments or measures of current conditions as well as how a policy, project, or action is likely to affect an ecosystem. Conceptual diagrams, also known as means-ends diagrams, are tools that can facilitate this process. Conceptual diagrams are made up of causal chains, also known as path models, which are logical models that declare how a management action or policy is expected to propagate through natural and social systems to effect changes in the provision of ecosystem services and benefits to various segments of society (For example Figure 2). As part of scoping, the causal chains embedded in conceptual diagrams may be preliminary best guesses requiring relatively little effort yet providing a comprehensive overview of all potentially significant services. Incorporating ecosystem services into conceptual diagrams can improve how agencies define problems and formulate solutions by expanding the focus of the decision maker beyond ecological outcomes to social outcomes caused by the ecological changes.3

Developing conceptual diagrams is a critical step to ensure that ecosystem services assessments are comprehensive and transparent.4

Conceptual diagrams incorporate all potentially significant causal chains for affected services. In doing so, they identify how a policy or management action can affect multiple aspects of an ecosystem and how each of the impacts on an ecosystem can have multiple impacts on social benefits (Figure 2). Creation of these diagrams forces the users to recognize intermediate ecological structures or processes and connections to nontarget ecological and ecosystem service outcomes. This process often leads to a richer (if more complicated) view of the system as new branches and paths are elaborated in iterative discussions of experts and stakeholders. These diagrams can help identify potential tradeoffs, or unintended consequences.5 They can also be used to compare the outcomes of management in different places. Such spatial analysis can be incorporated into geographic information system models. When assessing a policy or management action a conceptual diagram should be created for each distinct option (policy, management, or project alternative). This process may reveal that particular options are unlikely to impact services of interest. Those options could then be eliminated from further analysis. Constructing conceptual diagrams forces managers to embrace the complexity of the systems they manage and to identify gaps in understanding how ecosystem components and environmental benefits are linked.

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram with causal chains for an ecosystem services assessment of a forest management decision

Note: This conceptual map of simplified causal chains shows possible outcomes from forest fire management activities like mechanical thinning. Black text indicates an ecological assessment and indicators, red text indicates extension to an ecosystem services assessment, and blue text indicates measures of social benefit and value.

In considering possible impacts of management actions or policies on ecosystem services, it might be tempting to refer to a “master list” of services to help ensure that the conceptual diagram is complete. Such lists are often created in an effort to classify ecosystem services.6 Generic lists of services can provide a useful starting point for considering which services and beneficiaries are relevant in a decision context, but given context-specific variation in services, generic classifications will almost always be insufficient and can often be misleading. Rather than or in addition to using classification systems, agencies should use causal chains and conceptual maps to identify ecosystem services and the groups potentially affected by agency actions for each decision.

Analysis

The analysis uses the outputs of the scoping processes, desired ecological conditions and social outcomes (i.e., ecosystem services), and the suite of management, project, or policy options that make it through the scoping process. Ecosystem services analysis estimates the effects of management or policy on the production of ecosystem services using measures of ecosystem changes that matter to people.

Selecting Services for Further Analysis

Developing an initial conceptual diagram is useful for considering all possible impacts to valued services. This process will likely identify too many services to be meaningfully quantified in any ecosystem services assessment. Thus, the quantitative assessment can focus on only those effects likely to be most important to the decision—often those expected to have the largest impacts on ecological processes and human welfare. Assessors can use a few key questions to determine which services should be included:

- Does the ecosystem service fall under the legal mandate of the assessor?

- Is the impact on the ecosystem service likely to be large and strongly driven by the proposed activity or decision?

- Will the expected changes to the ecosystem service matter to or affect the social welfare of many people or groups of special concern?

By proceeding in this manner, the agency acknowledges the full suite of affected ecosystem services and can be more transparent about the services that are (and are not) subsequently analyzed and the rationale for these decisions. A full empirical assessment cannot and likely should not be conducted for all services initially identified in a conceptual map. And indicators used as performance metrics likely cannot be monitored for all services.

Agencies may need to collaborate with one another to include ecosystem services outside their authorities in an empirical assessment or monitoring plan. This may be important if the service outside of agency authority experiences a significant change.

Causal Chains

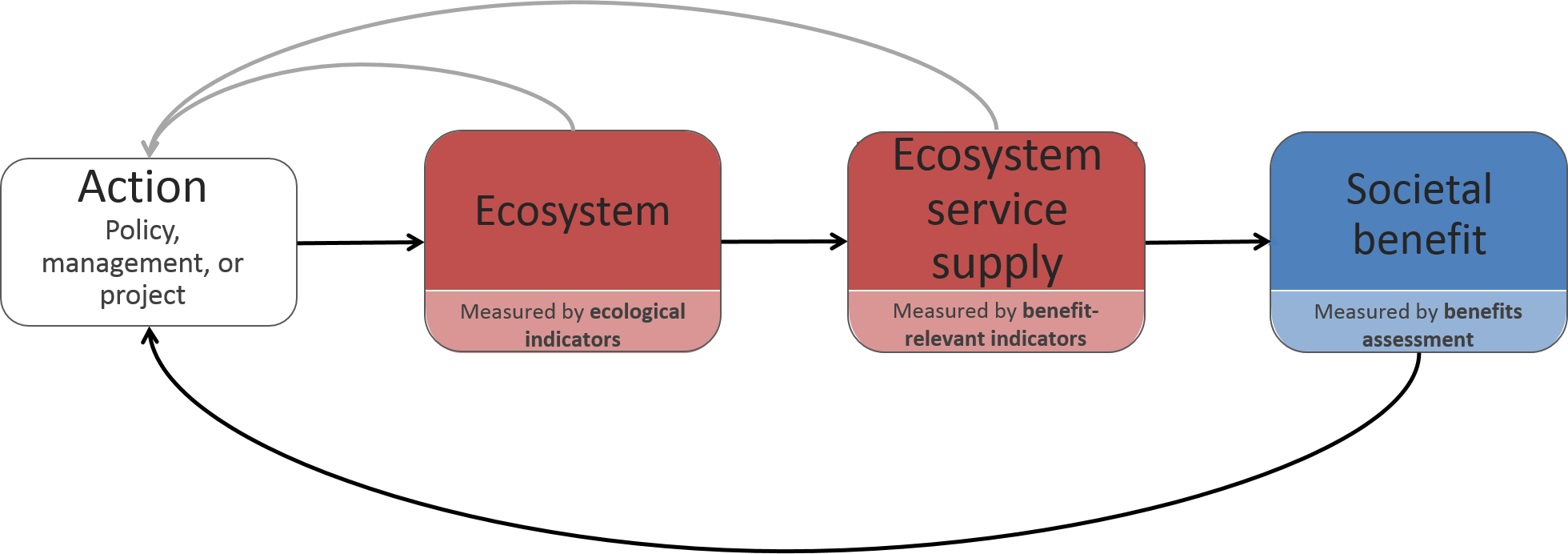

Causal chains are logic models that describe how actions propagate through systems to effect changes in outcomes. When used in ecological assessments, causal chains often end with expected environmental changes and stop short of including impacts on benefits to society. In contrast, a causal chain in an ecosystem services assessment follows through to effects on social outcomes and human well-being (Figure 3a,b). In the analysis, the causal chains sketched out during the scoping process in conceptual diagrams that are selected as important are now more fully developed. Developing robust quantifiable causal chains is a critical step to ensure that ecosystem services assessments are comprehensive and transparent. 7

Constructing causal chains forces managers to identify gaps in knowledge, data, and modeling capacity as well as in understanding how ecosystem components are linked.

Figure 3. Example causal chains

(a) Components of an ecosystem service causal chain

(b) Example of an ecosystem services causal chain for wetland restoration and water availability for crops

The process of creating causal chains and conceptual diagrams evolves during the analytical process. It may start conceptually, but then indicators are added to make the concepts measureable, followed by the insertion of data, and ultimately it can become the template for a data-driven model used to estimate changes in services expected from a policy or management action (Figure 3b). The indicators identified in the causal chains can be used to monitor changes or assess performance against an objective (e.g., performance metrics).

Benefit-Relevant Indicators

Ecosystem services assessment, at minimum, requires measures of ecosystem changes that matter to people. To quantify these changes we need to use what we call benefit-relevant indicators (BRIs). BRIs are measurable indicators that capture the connection between ecosystems and people by considering whether there is demand for an ecosystem service, how much it is used (for use values including services that reduce risks) or enjoyed (for nonuse values), and whether the site provides the access necessary for people to benefit from the service, among other considerations. Many indicators used to capture ecological changes are not easily appreciated by stakeholders as being of direct relevance to personal values or well-being. Chlorophyll or nitrogen concentrations might be good indicators of water quality, but most stakeholders would have little appreciation for or place any particular value on these indicators. Instead, they might simply want to know whether the water is fishable or swimmable.

The analysis phase of an ecosystem services assessment quantifies changes in ecosystem services using BRIs identified in causal chains. BRIs can be used directly in an intuitive decision-making process or as an input into a formal evaluation process in which preferences are quantified through monetary or nonmonetary methods (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Questions to guide an ecosystem services analysis using benefit-relevant indicators

Note: Intuitive comparisons require decision makers to use their knowledge of preferences (stakeholder or institutional) implicitly, rather than to assess them explicitly.

Agencies should use the information in the guidebook to select which of these methods fit their decision-making needs—for example using benefit-relevant indicators alone to estimate changes to the supply of services if monetary valuation or multicriteria decision analysis are not feasible. Choosing an assessment technique requires evaluating the type and accuracy of information required in a given policy context. For example, legal proceedings might require different standards from collaborative decision-making with stakeholders. Monetary valuation and multicriteria decision analysis can be used to characterize values and tradeoffs, whereas BRIs alone cannot. In addition, assessment techniques vary in terms of data requirements and the amount of time required, so the availability of funding and other resources will influence choice of methods. Fortunately, the development of BRIs can provide information that is directly relevant to any subsequent evaluation of social benefits, so that identification and potential quantification of BRIs is often useful whether or not there is a current plan to conduct monetary or nonmonetary valuation.

Quantifying BRIs Using Causal Chains

BRIs need to meet two criteria—(1) reflect changes that are relevant to beneficiaries and (2) where relevant capture some aspect of intensity of use and physical and institutional access. BRIs also need to be well-defined measures that are easily reproducible or testable; descriptive narratives alone are not sufficient and cannot be used in assessments of value.

To quantify the change in ecosystem service provision (the changes relevant to beneficiaries) using BRIs, causal chains must be converted into operational empirical models. There are several ways to estimate the relationship between an action (policy, project, management) and its effect on the production of services. One common example, ecological production functions, are ecological models that capture the responsiveness of ecosystem services provision to changes in the environment.

Identification and quantification of the people who could benefit from an ecosystem service—beneficiaries—and where needed, the constraints on access, involves defining the flows of services or servicesheds. 8

A serviceshed analysis is a spatial analysis that incorporates information on where services are produced (what ecosystem and location) and connects this to an assessment of where beneficiaries or risks are located (e.g., downstream, within the airshed, within a one-hour driving distance). For most ecosystem services decision makers need to know not only where these people are, but who they are, how many, and whether they are affected by potential changes in the provision of services (e.g., reduction in flood or fire frequency or intensity). Like other parts of an assessment process, identifying beneficiaries is an iterative process. Perhaps best guesses are used at the outset of the scoping process with more quantification during the analysis that feeds back to inform what stakeholders are engaged in the process.

As a general principle, the scale (geographic extent and time horizon) and types of beneficiaries in an assessment should be matched to the scale and the priority services affected by the decision or planning process. Decisions that affect very few services and only local services can be assessed on a local scale; plans that involve multiple services and geographically far-ranging beneficiaries must be assessed at more extensive spatial scales (and probably over a longer time). In the case of habitat supporting a rare species of mushroom, stakeholders might range from local mushroom collectors to people around the world for whom the mere existence of the species holds value. In many cases, beneficiaries are located beyond traditional boundaries and across jurisdictions. Information on the potential extent of service provision is relevant to an assessment of value and can also help identify beneficiaries, reveal gaps in service provision, or suggest locations where stakeholders might experience a degradation or loss of current services. This information could also highlight possible equity issues and further inform the decision process.

In selecting which BRIs to quantify, it is important to note that some BRIs are better at reflecting the most relevant information about an ecosystem service than others. The best BRIs will indicate a highly certain link between the environment and a human benefit and will also indicate the intensity of human use, enjoyment, or impact.

When directly assessing or monitoring the ecosystem service outcomes of an action (perhaps to track performance), a direct measure of a BRI can be used (e.g., number of fish caught by recreational anglers, abundance of iconic species, or number of hospitalizations from airborne particulates during wildfires). Monitoring and assessments need to use well-defined measures that are easily reproducible or testable; descriptive narratives alone are not sufficient.

If the analysis stops with estimated changes in BRIs, managers will have predicted percent or unit changes in measures that represent the outcomes most relevant to people (e.g., particulate levels in airshed and number of people exposed). Changes in these indicators can be incorporated into alternatives matrices to allow a side-by-side comparison of options and then integrated into the decision process (Table 1). While the insight that BRIs alone can provide into tradeoffs is limited, sometimes it is possible to see that one subset of alternatives results in more ecosystem service provision than others (assuming more is better) or that certain alternatives can maintain multiple services without significant losses.

The analysis process increases in complexity as analysts build a comprehensive picture of predicted changes in ecosystem services and social preferences, but it can also be simplified as alternatives are dropped. Alternatives are dropped as it becomes apparent that they (1) fail to achieve objectives, (2) produce few desired outcomes, (3) create unacceptable tradeoffs, or (4) are too expensive. Some of this winnowing may also be accomplished during the scoping stage, either through expert opinion (e.g., what is technically feasible through management) or by stakeholder consensus (e.g., outcomes nobody cares about). The rest will happen in the analytical process.

Assessing Social Benefits

BRIs capture information on the intensity of stakeholder interaction with services and the number or groups of stakeholders affected by the service. But BRIs do not directly capture stakeholder preferences or values for different levels of performance or provision of service, nor do they capture stakeholders’ relative preferences for different services or their willingness to trade one service off relative to another. Thus, formal evaluation of alternatives requires an assessment of benefits considering values or preferences via monetary or nonmonetary methods. An assessment of benefits is needed if (1) service provision varies substantially across different stakeholder populations (i.e., there are differences of opinion about the outcomes) or (2) changes in services in response to management or policy vary in direction (or magnitude) across services. In either case, tradeoffs will have to be made. When a decision involves tradeoffs (e.g., alternative policies that provide more of some services and less of others), it is often critical to understand the relative value people place on the different services. Otherwise, it is not possible to know which alternative policy option is preferable. Without an assessment of benefits, the analysis is left with conclusions regarding quantities of what is valued (e.g., irrigation water), without any information on how much they are valued (e.g., is more irrigation water worth the investment in wetland restoration?). In this guidebook, assessment of benefits refers to both economic valuation and nonmonetary multicriteria analysis. To clarify often-used terms, value is used in the economic sense to imply well-defined, generally monetary measures of value. Preference(s) is often used to reflect how individuals order outcomes on the basis of the relative satisfaction or enjoyment (i.e., utility) they provide rather than using monetary measures; outcomes that generate greater utility also generate greater value. If we align management with particular social values, we also need to consider the impacts of those choices on ecological integrity and the ability of the landscape to provide ecosystem services into the future.

Most regulatory impact analyses require economic valuation of some type, and many other types of federal decisions encourage or require some type of valuation. Office of Management and Budget guidance suggests that assessments of significant federal actions should monetize all primary effects that can be monetized.9 Monetary expressions of value are often preferred in federal decisions. Expressing all benefits in a common monetary metric allows for analysis of tradeoffs among services and a clear bottom line in terms of net benefits. However, there are limitations to the use of monetary values to express the value of ecosystem services. In some federal decision contexts, the role of economic values is expressly limited.10 In others, there is reluctance to monetize some kinds of ecosystem services, or the difficulty or expense of estimating monetary values may be large relative to agency resources.11 Other limitations arise from cultural or religious prohibitions on monetizing some kinds of ecosystem services; cultural values to tribes of spiritual and religious artifacts and sites are a frequently cited example.12 Nonmonetary methods can be used when dollar values are not desired and when understanding the differences among multiple stakeholder groups’ preferences is preferable to the quantification of economic values.

BRIs are important and desirable inputs to assessments of benefits because the measure being valued needs to capture and be responsive to how stakeholders use, interact with, and appreciate ecological outcomes.13 Hence, BRIs often serve as ideal inputs into models used for valuation.

Methods for economic valuation have been developed and evaluated over the past five decades and are well established in both the scientific literature and guidance documents.14 Protocols and standards for these methods document the circumstances in which different types of valuation methods are appropriate. An economist trained in monetary valuation can help decision makers ensure that the translation from BRIs to values is based on the application of valid and reliable methods.

Similarly, methods for multicriteria decision analysis are described in a handbook developed by the London School of Economics to advise local governments on use of multicriteria analysis.15 Several books address practical applications of these methods, and a primer has been developed to accompany this guidebook.16 In addition, the U.S. Geological Survey and other federal agencies have developed instructional materials on structured decision making that enable training of agency personnel.17 People who have participated in this training can be called on by agencies that want to apply these tools for nonmonetary valuation of ecosystem services.

Other approaches to estimate stakeholder preferences include using qualitative estimates of preferences. “Popularity votes” by stakeholders solicited through meetings or electronic forums or by decision makers acting on behalf of stakeholders by proxy may be useful for engaging stakeholders in the scoping stage of an assessment. However, these methods are not viewed by experts as sufficient to determine values or preferences for a formal analysis.

It is important to keep in mind that values are context dependent, as are decisions.

The Decision Process

When comparing alternatives, measures of changes in ecosystem services—what is valued (BRIs) or how much they are valued (dollar values or relative satisfaction)—can be organized by ecosystem service and management into an alternative or decision matrix (Table 1). The alternatives matrix is a summary of the state of knowledge for a management decision: what is known about the ecosystem and how it might respond to management, stakeholders’ preferences for those changes, and analysts’ confidence in that information.

When BRIs (in a variety of different units) or multiple types of measures (BRIs and dollars) populate an alternatives matrix, it is difficult for managers to consider changes in services or benefits on an equal footing. This places additional burden on a decision maker especially if there are tradeoffs across services or values. Communication of impacts in a single, directly comparable metric (e.g., money in the case of effects valued using economic valuation) alleviates these “apples versus oranges” comparisons. If economic valuation or multicriteria evaluation is used to assess social impact, aggregated values for each alternative may be the primary outcome of interest, but it could be accompanied by an alternatives matrix to provide greater transparency.

Table 1. Example of an alternatives matrix

Ideally an alternatives matrix will be accompanied by information about what was included and what was excluded from the assessment, analysis, or both as well as information about participants in each step, data used and data gaps, assumptions and uncertainties, and an explanation of discarded options. This information increases the transparency of the decision process and facilitates communication of information to stakeholders. Of course, other information will also inform the decision process, including agency mandates and legal authority, cost allocations, local economic effects, and distributional implications (equity). Because these considerations are not particular to the use of ecosystem services considerations in decision making, they are not elaborated on here. The use of alternatives matrices can communicate information on uncertainty, support objective decision making, and increase the transparency of the decision process. This summary can be a powerful communications tool for managers and stakeholders.

Providing information on the flow of ecosystem services benefits to stakeholders creates an opportunity for an analysis of the distributional implications of management or policy decisions on different demographic groups, communities, or generations. Such analysis can answer questions such as: Who benefits? Does the relative flow of services to different communities raise equity or environmental justice issues? Are the flows of services sustainable?

The result of a decision process is often that a particular management activity or set of activities is selected as the preferred option and implemented.

Evaluation and Reaction

The adaptive management cycle—plan, act, monitor, react—presumes that the consequences of management actions are monitored. This monitoring often addresses implementation itself: in prescribed fire, managers monitor how effectively the burn was administered; in wetland mitigation, managers monitor the success of restoration activities (e.g., the establishment and short-term survival of plantings). Less frequently, managers monitor the ecological effects or outcomes of these activities: whether the prescribed fire reduced the incidence of catastrophic fire (e.g., crowning of surface fire) or whether wetland mitigation activities had the desired effect on hydrology, biogeochemistry, or wetland species composition. In short, managers often monitor their management actions but rarely monitor actual desired ecological outcomes—much less ecosystem-derived benefits, which would require tracking BRIs.

On the other hand, social benefits can be monitored directly via proxies (e.g., by counting visitors), but assessing benefits often requires surveys especially for services with nonuse values, which may be difficult for federal agencies to implement.

However, it might be feasible to monitor the ecological indicators on which social benefits depend—the BRIs. An ecosystem services assessment process, with development of causal chains with BRIs, provides an opportunity for managers to identify important BRIs and incorporate them into monitoring programs. Whenever possible, such indicators should be supplemented with information on access and other factors that affect the benefits produced. Such indicators can be used as performance metrics that will assess how programs or projects are doing in terms of achieving goals on the provision or maintenance of particular services and benefits.

The result of this monitoring informs future actions in two ways. First, monitoring of actual management outcomes (whether social benefits, BRIs, or ecological outcomes) provides information on the effectiveness of those actions and therefore provides direct feedback to future management decisions and helps agencies develop more meaningful performance measures. It will also inform development of ecological models of management effects (ecological production functions) that are needed for quantitative ecological assessments. It also feeds back explicitly to the scoping stage of the next planning process, in which management alternatives are weighed in terms of desired outcomes, closing the adaptive management loop.

Monitoring indicators of outcomes rather than management actions can also help agencies update regional status and trends to reflect ecological conditions and flows that are important to people. This information, in turn, would revise the context for future management decisions.

Recommended Reading

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2002. A Framework for the Economic Assessment of Ecological Benefits. http://www.epa.gov/stpc/pdfs/feaeb3.pdf.

This EPA framework integrates ecological risk assessment and economics. It covers in greater depth some of the methods presented in this guidebookbut is primarily focusedon economic analysis.

Boyd, J.W., and S. Banzhaf. 2007. “What Are Ecosystem Services? The Need for Standardized Environmental Accounting Units.” Ecological Economics 63: 616–626.

This article links the concept of final ecosystem goods and services to ecological and social impact analysis or accounting. This concept is used by many agencies and is consistent with the framework presented in this guidebook.

Gregory R., L. Failing, M. Harstone, G. Long, T. McDaniels, and D. Ohlson. 2012. Structured Decision Making: A Practical Guide to Environmental Management Choices. 1st ed. Chichester, UK: R. Blackwell Publishing.

This book describes the use of structured decision making for real-world environmental decision making, involving multiple stakeholders. It is not a “how-to” manual.

Office of Management and Budget. 2003. Circular A-4. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/regulatory_matters_pdf/a-4.pdf.

This memo provides guidance to federal agencies on standard ways to measure and report the benefits and costs of regulatory action. Although not specific to ecosystem services, the memo explains how valuation should be used and identifies other methods for contexts in which valuation is not appropriate.

Ranganathan, J., C. Raudsepp-Hearne, N. Lucas, F. Irwin, M. Zurek, K. Bennett, N. Ash, and P. West. 2008. “Ecosystem Services: A Guide for Decision Makers.” Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute. http://pdf.wri.org/ecosystem_services_guide_for_decisionmakers.pdf.

An introductory guide that discusses the links between development and ecosystem servicers. It includes a general list of ecosystem services on p. 23-24, but does not connect these to beneficiaries. It also provides a high level screening process for assessing risks and opportunities related to ecosystem services p30.

Ruckelshaus, M., E. McKenzie, H. Tallis, A. Guerry, G. Daily, P. Kareiva, S. Polasky, T. Ricketts, N. Baghabati, S. Wood, and J. Bernhardt. 2013. “Notes from the Field: Lessons Learned from Using Ecosystem Services to Inform Real-World Decisions.” Ecological Economics. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.009. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800913002498.

This article reviews 20 ecosystem services applications to assess how they informed or influenced decisions. It provides information on when simple models and approaches can be most useful.

Footnotes

- See, e.g., K.J. Bagstad, D. Semmens, R. Winthrop, D. Jaworski, and J. Larson, “Ecosystem Services Valuation to Support Decisionmaking on Public Lands: A Case Study of the San Pedro River Watershed, Arizona,” U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5251 (2012), http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2012/5251/; E. Nelson, G. Mendoza, J. Regetz, S. Polasky, H. Tallis, D.R. Cameron, K.M.A. Chan, G.C. Daily, J. Goldstein, P.M. Kareiva, E. Lonsdorf, R. Naidoo, T.H. Ricketts, and M.R. Shaw, “Modeling Multiple Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity Conservation, Commodity Production, and Tradeoffs at Landscape Scales,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7 (2009): 4–11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/080023.

Back to reading ↩ - See J.S. Hammond, R.L. Keeney, and H. Raiffa, Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Decisions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1999); U. S. National Research Council, Understanding Risk: Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1996);L. Gregory, M. Failing, G. Hartsone, T. Long, T. McDaniels, and D. Ohlson, Structured Decision Making: A Practical Guide to Environmental Management Choices(Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2012).

Back to reading ↩ - See, e.g., K.J. Bagstad, D. Semmens, R. Winthrop, D. Jaworski, and J. Larson, “Ecosystem Services Valuation to Support Decisionmaking on Public Lands: A Case Study of the San Pedro River Watershed, Arizona,” U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5251 (2012), http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2012/5251/; E. Nelson, G. Mendoza, J. Regetz, S. Polasky, H. Tallis, D.R. Cameron, Kai MA Chan, G. C. Daily, J. Goldstein, P.M. Kareiva, E. Lonsdorf, R. Naidoo, T.H. Ricketts, and M.R. Shaw, “Modeling Multiple Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity Conservation, Commodity Production, and Tradeoffs at Landscape Scales,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7 (2009): 4–11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/080023.

Back to reading ↩ - For more information on final ecosystem goods and services, see J. Boyd and S. Banzhaf, “What Are Ecosystem Services? The Need for Standardized Environmental Accounting Unites.” Ecological Economics 63 (2007): 616-626. and D.H. Landers and A.M. Nahlik, “Final Ecosystem Goods and Services Classification System (FEGS-CS), “EPA/600/R-13/ORD-004914, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Corvallis, Oregon (2013), http://gispub4.epa.gov/FEGS/FEGS-CS%20FINAL%20V.2.8a.pdf.

Back to reading ↩ - See, e.g., K.J. Bagstad, D. Semmens, R. Winthrop, D. Jaworski, and J. Larson, “Ecosystem Services Valuation to Support Decisionmaking on Public Lands: A Case Study of the San Pedro River Watershed, Arizona,” U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5251 (2012), http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2012/5251/; E. Nelson, G. Mendoza, J. Regetz, S. Polasky, H. Tallis, D.R. Cameron, K.M.A. Chan, G.C. Daily, J. Goldstein, P.M. Kareiva, E. Lonsdorf, R. Naidoo, T.H. Ricketts, and M.R. Shaw, “Modeling Multiple Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity Conservation, Commodity Production, and Tradeoffs at Landscape Scales,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7 (2009): 4–11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/080023.

Back to reading ↩ - Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005); Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (2013), http://cices.eu/.; D.H. Landers and A.M. Nahlik, Final Ecosystem Goods and Services Classification System (FEGS), EPA/600/R-13/ORD-004914, 2013, http://ecosystemcommons.org/sites/default/files/fegs-cs_final_v_2_8a.pdf; P. Sinha and G. Van Houtven, National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application, draft report prepared for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Back to reading ↩ - National Ecosystem Services Partnership. 2016. Federal Resource Management and Ecosystem Services Guidebook. 2nd ed. Durham: National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Duke University, https://nespguidebook.com.

Back to reading ↩ - Tallis, S. Polasky, J.S. Lozano, and S. Wolny, “Inclusive Wealth Accounting for Regulating Ecosystem Services,” in Inclusive Wealth Report 2012: Measuring Progress towards Sustainability (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Back to reading ↩ - Office of Management and Budget, Guidance on Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2003, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/regpol/circular-a-4_regulatory-impact-analysis-a-primer.pdf.

Back to reading ↩ - Examples include the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and sections of the Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act, among many others. See K.J. Arrow, M.L. Cropper, G.C. Eads, R.W. Hahn, L.B. Lave, R.G. Noll, P.R. Portney, M. Russell, R. Schmalensee, V.K. Smith, and R.N. Stavins, “Is There a Role for Benefit Cost Analysis in Environmental, Health and Safety Regulation?,” Science 272 (1996): 221–222. A detailed, illustrative discussion of this issue in the context of fish stock rebuilding is provided by Committee on Evaluating the Effectiveness of Stock Rebuilding Plans of the 2006 Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act, Evaluating the Effectiveness of Fish Stock Rebuilding Plans in the United States (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014).

Back to reading ↩ - L. Wainger and M. Mazzotta, “Realizing the Potential of Ecosystem Services: A Framework for Relating Ecological Changes to Economic Benefits,” Environmental Management 48 (2011): 710–733.

Back to reading ↩ - R. Winthrop, “The Strange Case of Cultural Services: Limits of the Ecosystem Services Paradigm,” Ecological Economics 108 (2014): 208–214.

Back to reading ↩ - Evaluation sometimes refers only to economic or monetary valuation methods. In this case, it includes monetary and nonmonetary multicriteria methods. Both approaches include the preferences and values of people; they just use different units (e.g., dollars versus utilities) to do so.

Back to reading ↩ - P.A. Champ, K.J. Boyle, and T.C. Brown, A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation: The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources(New York: Springer, 2003); A.M. Freeman, J.A. Herriges, and C.L. Kling, The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: RFF Press, 2014); D.S. Holland, J.N. Sanchirico, R.J. Johnston, and D. Joglekar, Economic Analysis for Ecosystem-Based Management: Applications to Marine and Coastal Environments (Washington, DC: RFF Press, 2010); National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Federal Resource Management and Ecosystem Services Guidebook(Durham: National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Duke University, 2014), https://nespguidebook.com; Office of Management and Budget, Guidance on Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2003, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/regpol/circular-a-4_regulatory-impact-analysis-a-primer.pdf; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Policy, National Center for Environmental Economics, Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses, 2014, http://yosemite.epa.gov/ee/epa/eerm.nsf/vwAN/EE-0568-50.pdf/$file/EE-0568-50.pdf; Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and National Marine Fisheries Service, Guidelines for Economic Review of National Marine Fisheries Service Regulation Actions, 2007, http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/domes_fish/EconomicGuidelines.pdf.

Back to reading ↩ - Department of Communities and Local Government, Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual, 2009, www.communities.gov.uk. See appendices 1 to 8.

Back to reading ↩ - R. Gregory, L. Failing, M. Harstone, G. Long, T. McDaniels, and D. Ohlson, Structured Decision Making: A Practical Guide to Environmental Management Choices (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

Back to reading ↩ - URL: http://nctc.fws.gov/courses/SDM/home.html.

Back to reading ↩