Overview of Benefits Assessment

This section is adapted from the paper “Best Practices for Integrating Ecosystem Services into Federal Decision Making” and combined with content from the first version of the FRMES online guidebook.

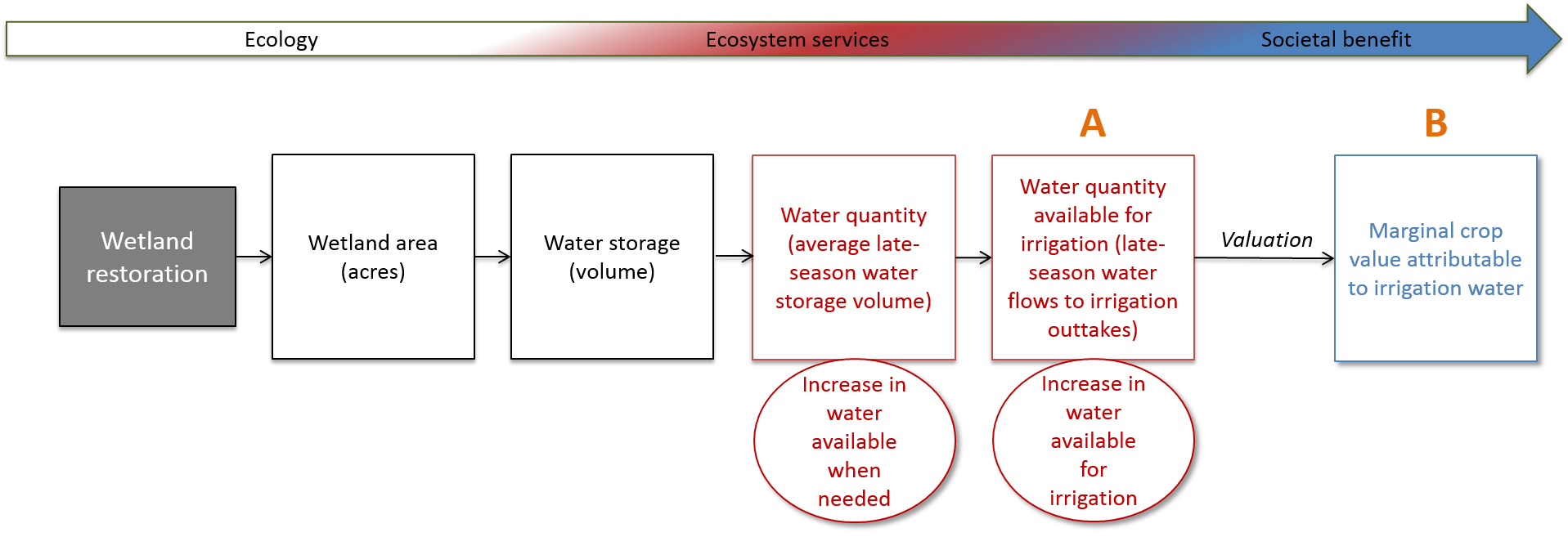

Information (for a formal analysis) or assumptions (for an intuitive decision) about social preferences or values are essential for decision makers to draw conclusions about how changes in the provision of ecosystem services will affect societal benefits. Even “more is better” conclusions require decision makers to assume a universally positive relationship between services and social welfare. When a decision involves tradeoffs (e.g., alternative policies that provide more of some benefit-relevant indicators (BRIs) and less of others), it is critical to understand the relative value people place on the different services. Otherwise, it is not possible to know which alternative policy option is preferable. Without benefits assessment, the analysis is left with conclusions regarding quantities of what is valued (e.g., irrigation water) (Figure 1, box A), without any information on how much they are valued (e.g., is more irrigation water worth the investment in wetland restoration?) (Figure 1, Box B). Here, benefits assessment refers to a broad set of analytical methods, including both economic valuation and nonmonetary multicriteria analysis. While the term value can be used broadly, it is defined more narrowly in this framework to distinguish the methods commonly used. Value is used in the economic sense to imply well-defined, generally monetary measures of value. Preference(s) is used to reflect how individuals order outcomes on the basis of the relative satisfaction or enjoyment (i.e., utility) they provide; outcomes that generate greater utility also generate greater value.

Figure 1. Ecosystem services supply measured as a benefit-relevant indicator (BRI) (quantities of what is valued, A) and social benefit (how much the service is valued, B)

Note: The black text shows the ecological assessment and indicators; the red text shows the transition to ecosystem services assessment, with BRIs shown in the circles; and the blue text shows the final benefit as a value.

“Marginal” refers to a small additional change to an existing quantity. Consequently, marginal crop value would refer to the additional crop value provided by the action under study.

Although we consider quantification with BRIs to be minimum best practice, an ecosystem services analysis will always be more informative when rigorous information on values or preferences is included. A benefits assessment is helpful because a policy that influences a greater number of services is not necessarily superior to a policy that influences fewer. And more of a service is not always better. An increasing quantity of water in a river used for recreation will be a benefit up to a point but becomes a problem once the river begins to flood (i.e., value is not always a monotonic function of ecosystem service quantity). Benefits assessment can help ensure that assessors make appropriate inferences regarding the effect of changes in services on human wellbeing. One way of expressing people’s preference for a given level of service, or for one service as compared to another, is in monetary terms (economic valuation); another is to form a unitless ranking (using nonmonetary methods).

Most regulatory impact analyses require economic valuation of some type, and many other types of federal decisions encourage or require some type of valuation. Office of Management and Budget guidance suggests that assessments of significant federal actions should monetize all primary effects that can be monetized.1 Monetary expressions of value are often preferred in federal decisions. Expressing all benefits in a common monetary metric allows for analysis of tradeoffs among services and a clear bottom line in terms of net benefits. However, there are limitations to the use of monetary values to express the value of ecosystem services. In some federal decision contexts, the role of economic values is expressly limited.2 In others, there is reluctance to monetize some kinds of ecosystem services, or the difficulty or expense of estimating monetary values may be large relative to agency resources.3 Other limitations arise from cultural or religious prohibitions on monetizing some kinds of ecosystem services; the cultural value that tribes place on spiritual and religious artifacts and sites is a frequently cited example.4 Nonmonetary methods can be used when dollar values are not desired and when an understanding of the differences among multiple stakeholder groups’ values is preferable to the quantification of economic values.

Economic Valuation

Estimation of economic values, including both market and nonmarket values, enables an ecosystem services analysis to:

- Identify options that are socially beneficial (or optimal) from the broader set that are feasible,

- Provide a more informative analysis of tradeoffs, including benefits and costs realized by different affected groups (who gains and who loses and how much they gain or lose),

- Demonstrate whether the economic benefits of agency actions (including benefits realized outside of markets) outweigh the costs (benefit-cost analysis), and

- Inform the design of market-based programs to encourage provision of ecosystem services (payments for ecosystem services). For example, estimation of economic values can identify which types of users would be willing to pay to access or use ecosystem services of various types.

Methods for economic valuation have been developed and evaluated over the past five decades and are well established in both the scientific literature and guidance documents (see Monetary Valuation section).5 Protocols and standards for these methods document the circumstances in which different types of valuation methods are appropriate. Valuation can be conducted at differing levels of accuracy, depending on the reasons for the analysis as well as data, time, and expertise available to conduct the analysis.6 The level of accuracy may also be determined by required regulatory approvals (e.g., the Office of Management and Budget requires approvals for many types of data collection and regulatory analyses).7 Economic valuation can be conducted alongside other forms of preference evaluation, to provide multiple perspectives on social value and preference.

An economist trained in monetary valuation can help decision makers ensure that the translation from BRIs to values is based on the application of valid and reliable methods. Valuation can be accomplished using a primary study at the site of interest (generating new valuation data and results) or with benefit transfer. Benefit transfer uses research results from preexisting primary valuation studies at one or more sites or policy contexts (often called study sites) to predict economic values at other, typically unstudied, sites or policy contexts (often called policy sites).8 Primary data collection is more accurate but generally requires more time and resources to conduct.9 In either case, specific methods are required to ensure that values meet minimum standards for validity and accuracy.10 Only a subset of possible monetary measures associated with ecosystem services may be interpreted as measures of economic value. In the absence of the expertise required to conduct economic valuation methods, to evaluate them, or both, it is generally preferable to refrain from valuation (i.e., stop the analysis at the quantification of BRIs) rather than to generate values with unknown or questionable validity and accuracy.

Establishing the Link between BRIs and Economic Valuation

BRIs, if chosen appropriately, serve as the necessary ecological or biophysical inputs into economic valuation models; they are the measures that link biophysical measures or models to valuation estimates or models. That is, BRIs reflect the things that generate benefits or that are valued (directly or indirectly) within an economic valuation study. A carefully developed causal chain (or conceptual diagram) and a comprehensive set of BRIs associated with any policy action can also help analysts identify all the ways that the action might influence social value—whether through market or nonmarket channels. In this way, the use of BRIs can help ensure that values of nonmarket ecosystem services are appropriately recognized.

As noted in “Quantifying BRIs,” superior BRIs will be “closer” to the final services that provide value to people and hence better suited to valuation. That is, valuation models are more accurate and less subject to bias when the included variables are those that directly (rather than indirectly) influence values and behavior.11 The economic literature provides guidance on the choice of specific BRIs for different types of revealed and stated preference valuation, although these works do not necessarily use the “BRI” terminology.12 Different BRIs will generally link to different values realized by different beneficiary groups. Hence, the most appropriate BRIs for use within any particular valuation model will depend on the type of value being estimated and the type of valuation model being used. This information is the same as that required to define any BRI, regardless of whether valuation will be conducted. For example, an analysis of recreational fishing values would require information on BRIs directly relevant to the behavior and values of recreational anglers such as changes in average or expected harvest rates of targeted species (See “Choosing the Best BRI” Figure 2).

Accounting for Scope and Scale in Monetary Valuation

Economic values are meaningful only for a particular quantity of a market or nonmarket commodity, relative to a specific baseline. In other words, they are only meaningful when valuing a specific change in the provision of a service. If the change is large (i.e., nonmarginal), value estimation must account for the fact that per-unit values for any commodity generally diminish as more of that commodity is obtained (a phenomenon referred to as diminishing marginal utility, where utility is the amount of benefit obtained). For example, a recreational angler is generally willing to pay more per fish to increase her catch from 0 to 1 fish than from 99 to 100 fish; the value of a marginal fish depends on how many fish have already been caught.13 In most cases, the change in a BRI cannot be multiplied by a simple “unit value” to arrive at a total value of the change (at least for nonmarginal changes); doing so would overlook the fact that marginal values tend to diminish as quantity or quality increases. Similarly, values per unit of area (e.g., per acre) generally cannot be calculated and multiplied by the total affected area.

Consequently, applying values determined for one scale of change to another scale of change is inappropriate, making it difficult to estimate regional or national values from local values. In a small number of cases, value scaling may be feasible. An example would be small-scale localized changes in a good valued due to its global consequences (or because it is sold on global markets), such as changes in local greenhouse gas emissions. An economist trained in valuation can help determine whether and how value scaling is (or is not) appropriate in particular valuation contexts.

Nonmonetary Multicriteria Analytical Methods

When monetization of all or some of the ecosystem services measures in an analysis is inappropriate or too difficult to do well, assessors can use a variety of analytical methods with both monetized and nonmonetized components to develop a ranking or rating of alternatives with respect to their contributions to stakeholder preferences for ecosystem services. Several of these methods are described in a handbook developed by the London School of Economics to advise local governments on use of multicriteria analysis.14 Some of the methods (e.g., outranking procedures and the Analytical Hierarchy Process) are less demanding of information on both performance of management alternatives and expressions of preference than others (e.g., multiattribute utility analysis, or MAUA), but they are correspondingly less transparent and thus less informative for the kinds of multiparty deliberative decision making that often characterizes resource management.15 Although MAUA has been criticized as too time-consuming and too dependent on expertise that agencies may not have, it has the advantage of obliging users to think carefully about all the elements of preference evaluation in a systematic way. There is value in using MAUA concepts to inform decision making when incorporating ecosystem services, even when a full quantification does not appear feasible.

Multicriteria analysis can be used for resource management problems such as impact assessment, in which one alternative must be selected; for resource allocation among potential activities; and for prioritization of targets for action (such as candidates for ESA listing). The stakeholder group selected to assign relative utility to ecosystem services outcomes (or BRIs) will vary depending on whether the agency is aiming to assess general public preferences or to fulfill select mission goals. MAUA will only be considered representative of public preferences if representative members of the public are included. Processes that occur within agencies can only be said to represent agency goals.

Multicriteria analysis has been used in various federal decision contexts, such as in National Estuary Program planning in Oregon and remedial planning for contaminated sites.16 It is useful for comparison of preferences among alternatives but not for estimations of value in any absolute sense. The components and results of analysis are tied to the decision context, including the items being evaluated (e.g., alternative management plans) and the range of performance of those alternatives for each ecosystem service. Multicriteria analysis can be used at any scale from local to international, but it cannot readily be scaled up or down without a great deal of additional work to establish that preference information is relevant to contexts other than those for which preferences were originally gathered. It is particularly useful for decisions affecting multiple stakeholders and for public decisions requiring a transparent decision process.

BRIs and associated measurement scales represent the ecosystem services being pursued in a particular decision context. Multicriteria analysis assigns relative preferences to different levels of a single BRI (and these preferences can differ among stakeholders and among decision contexts) and different weights/priorities among multiple BRIs in order to create a single combined metric of overall contribution to ecosystem services.

Multicriteria evaluation and the accompanying primer on multicriteria analysis outline good practices for applying multiattribute utility analysis to a NEPA-type decision process, but the elements apply equally to other types of agency decision making.17 Several books also address practical applications of these methods.18 In addition, the U.S. Geological Survey and other federal agencies have developed instructional materials on structured decision making that enable training of agency personnel.19 People who have participated in this training can be called on by agencies that want to apply these tools for nonmonetary valuation of ecosystem services.

Context Dependency and Transferability of Stakeholder Values and Preferences

Both monetary valuation and multicriteria analysis are context dependent in ways that make it difficult to transfer values or preferences among case studies. In both, stakeholder preferences are expressed in terms that depend on the considered management alternatives relative to the stated or observed baselines. The stakeholders themselves are localized in space (people in different regions might have very different values) and in time (both at the time that the assessment is completed and to the extent that the planning horizon affects values). These situational particulars are, of course, precisely the particulars that should inform any decision. But they also are a drawback in that they imply that monetary valuation and multicriteria decision analyses must be conducted for every management decision—a substantial investment.

One response to the context dependency of value is to extrapolate the results of social impact or valuation studies from one or more study sites to unstudied sites that have sufficiently similar contexts. Within economic valuation, this approach is called benefit transfer, and it can be conducted using single values (e.g., average values) or transfer models that adjust values according to site differences. In all cases, analysts must match studies from which values or drawn or models are built as closely as possible to the ecological outcomes and decision contexts of interest. Once benefit transfer models are built, model variables are used to adjust values according to sociodemographic variables and degree of ecological change, among other variables. Best practices for conducting benefit transfer have been established and should be followed closely in all uses.

With multicriteria decision frameworks, the aim of any given project is to capture the richness of context dependencies as faithfully as possible. This aim does not lend itself readily to the transfer of results among studies. Extrapolation of study results has not been an objective of practitioners of decision analysis, and transfer methods are not well developed. Practitioners of both economic valuation and multicriteria analysis would consider generally transfer of results from one study to another as inappropriate when the decision context and site details cannot be closely matched, unless formal, quantitative models can establish that values from dissimilar sites and contexts are expected to be similar.20

Footnotes

- 1 Office of Management and Budget, Guidance on Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/regpol/circular-a-4_regulatory-impact-analysis-a-primer.pdf. Back to reading

- 2 Examples include the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and sections of the Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act, among many others. See K.J. Arrow, M.L. Cropper, G.C. Eads, R.W. Hahn, L.B. Lave, R.G. Noll, P.R. Portney, M. Russell, R. Schmalensee, V.K. Smith, and R.N. Stavins, “Is There a Role for Benefit Cost Analysis in Environmental, Health and Safety Regulation?,” Science 272 (1996): 221–222. A detailed, illustrative discussion of this issue in the context of fish stock rebuilding is provided by the Committee on Evaluating the Effectiveness of Stock Rebuilding Plans of the 2006 Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act, Evaluating the Effectiveness of Fish Stock Rebuilding Plans in the United States (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014). Back to reading

- 3 L. Wainger and M. Mazzotta, “Realizing the Potential of Ecosystem Services: A Framework for Relating Ecological Changes to Economic Benefits,” Environmental Management 48 (2011): 710–733. Back to reading

- 4 R. Winthrop, “The Strange Case of Cultural Services: Limits of the Ecosystem Services Paradigm,” Ecological Economics 108 (2014): 208–214. Back to reading

- 5 P.A. Champ, K.J. Boyle, and T.C. Brown, A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation: The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources (New York: Springer, 2003); A.M. Freeman, J.A. Herriges, and C.L. Kling, The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: RFF Press, 2014); D.S. Holland, J.N. Sanchirico, R.J. Johnston, and D. Joglekar, Economic Analysis for Ecosystem-Based Management: Applications to Marine and Coastal Environments (Washington DC: RFF Press, 2010); National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Federal Resource Management and Ecosystem Services Guidebook (Durham, NC: National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Duke University, 2014), https://nespguidebook.com; Office of Management and Budget, Guidance on Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/regpol/circular-a-4_regulatory-impact-analysis-a-primer.pdf; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Policy, National Center for Environmental Economics, Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses, 2014, http://yosemite.epa.gov/ee/epa/eerm.nsf/vwAN/EE-0568-50.pdf/$file/EE-0568-50.pdf; Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and National Marine Fisheries Service, Guidelines for Economic Review of National Marine Fisheries Service Regulation Actions, 2007, http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/domes_fish/EconomicGuidelines.pdf. Back to reading

- 6 With respect to reason for the analysis, more accurate values are required for some types of applications. See J.D. Kline and M.J. Mazzotta, Evaluation of Tradeoffs among Ecosystem Services in the Management of Public Lands, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, General Technical Report PNW-GTR-865, 2012, http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr865.pdf. Back to reading

- 7 R. Iovanna and C. Griffiths, “Clean Water, Ecological Benefits, and Benefits Transfer: A Work in Progress at the U.S. EPA,” Ecological Economics 60(2)(2006): 473–482. Back to reading

- 8 R.J. Johnston and R.S. Rosenberger, “Methods, Trends and Controversies in Contemporary Benefit Transfer,” Journal of Economic Surveys 24 (2010): 479–510; R.J. Johnston, J. Rolfe, R.S. Rosenberger, and R. Brouwer, Benefit Transfer of Environmental and Resource Values: A Guide for Researchers and Practitioners (Netherlands: Springer, 2015). Back to reading

- 9 B. Allen and J. Loomis, “The Decision to Use Benefit Transfer or Conduct Original Valuation Research for Benefit-Cost and Policy Analysis,” Contemporary Economic Policy 26(1)(2008): 1–12. Back to reading

- 10 R.J. Johnston, J. Rolfe, R.S. Rosenberger, and R. Brouwer, Benefit Transfer of Environmental and Resource Values: A Guide for Researchers and Practitioners (Netherlands: Springer, 2015); A.M. Freeman, J.A. Herriges, and C.L. Kling, The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: RFF Press, 2014). Back to reading

- 11 J. Boyd and A. Krupnick, “Using Ecological Production Theory to Define and Select Environmental Commodities for Nonmarket Valuation,” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 42 (2013): 1–32; R.J. Johnston and M. Russell, “An Operational Structure for Clarity in Ecosystem Service Values,” Ecological Economics 70(12)(2011): 2243–2249. Back to reading

- 12 R.J. Johnston and M. Russell, “An Operational Structure for Clarity in Ecosystem Service Values,” Ecological Economics 70(12)(2011): 2243–2249; R.J. Johnston, E.T. Schultz, K. Segerson, E.Y. Besedin, and M. Ramachandran, “Enhancing the Content Validity of Stated Preference Valuation: The Structure and Function of Ecological Indicators,” Land Economics 88(1)(2012): 102–120; J. Boyd and A. Krupnick, “Using Ecological Production Theory to Define and Select Environmental Commodities for Nonmarket Valuation,” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 42 (2013): 1–32; P.L. Ringold, J. Boyd, D. Landers, and M. Weber, Report from the Workshop on Indicators of Final Ecosystem Services for Streams, EPA/600/R-09/137, 2009, http://www.epa.gov/nheerl/arm/streameco/docs/IndicatorsFinalWorkshopReportEPA600R09137.pdf; P.L. Ringold, A.M. Nahlik, J. Boyd, and D. Bernard, Report from the Workshop on Indicators of Final Ecosystem Goods and Services for Wetlands and Estuaries, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2011; P.L. Ringold, J. Boyd, D. Landers, and M. Weber, “What Data Should We Collect? A Framework for Identifying Indicators of Ecosystem Contributions to Human Well-Being,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11(2013):98–105, http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/110156; E.T. Schultz, R.J. Johnston, K. Segerson, and E.Y. Besedin, “Integrating Ecology and Economics for Restoration: Using Ecological Indicators in Valuation of Ecosystem Services,” Restoration Ecology 20(4)(2012): 304–310; M. Zhao, R.J. Johnston, and E.T. Schultz, “What to Value and How? Ecological Indicator Choices in Stated Preference Valuation,” Environmental and Resource Economics 56(1)(2013): 3–25. Back to reading

- 13 R.J. Johnston, M.H. Ranson, E.Y. Besedin, and E.C. Helm, “What Determines Willingness to Pay per Fish? A Meta-Analysis of Recreational Fishing Values,” Marine Resource Economics 21(1)(2006): 1–32. Back to reading

- 14 Department of Communities and Local Government, Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual, 2009, www.communities.gov.uk. See appendices 1 to 8. Back to reading

- 15 Department of Communities and Local Government, Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual, 2009, www.communities.gov.uk. See outranking procedures in appendices 6 and 7, the analytical hierarchy process in appendix 5, and multiattribute utility analysis in appendices 3 and 4. Back to reading

- 16 J. Arvai and R. Gregory, “Testing Alternative Decision Approaches for Identifying Cleanup Priorities at Contaminated Sites,” Environmental Science Technology 37(8)(2003): 1469–1476; R. Gregory and K. Wellman, “Bringing Stakeholder Values into Environmental Policy Choices: A Community-Based Estuary Case Study,” Ecological Economics 39 (2001): 37–52; I. Linkov, A. Varghese, S. Jamil, T.P. Seager, G. Kiker, and T. Bridges, “Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: Framework for Applications in Remedial Planning for Contaminated Sites,” in Comparative Risk Assessment and Environmental Decision Making, ed. I. Linkov and A. Ramadan, 15–54 (Amsterdam: Kluwer, 2004). Back to reading

- 17 National Ecosystem Services Partnership. 2016. Federal Resource Management and Ecosystem Services Guidebook. 2nd ed. Durham: National Ecosystem Services Partnership, Duke University, https://nespguidebook.com; L. Maguire, “Multicriteria Evaluation for Ecosystem Services: A Brief Primer,” 2014, https://sites.nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/ecosystemservices/research/publications/. Back to reading

- 18 R. Gregory, L. Failing, M. Harstone, G. Long, T. McDaniels, and D. Ohlson, Structured Decision Making: A Practical Guide to Environmental Management Choices (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012). Back to reading

- 19 http://nctc.fws.gov/courses/SDM/home.html. Back to reading

- 20 Moeltner, K. and R.S. Rosenberger. 2014. Cross-Context Benefit Transfer: A Bayesian Search for Information Pools. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 96(2): 469-488. Johnston, R.J., and K. Moeltner. 2014. Meta-Modeling and Benefit Transfer: The Empirical Relevance of Source-Consistency in Welfare Measures. Environmental and Resource Economics 59(3): 337-361. Back to reading